As I’ve been thinking about the erotic dimensions of psychedelic experience, I’ve found that current and classical definitions of erōs and eroticism, while useful, do not quite capture the meaning or sense I wish to convey. Part of the issue lies in the fact that most definitions of eroticism group it together with love on the one hand, and sex on the other. But can we define erōs, eroticism, and especially the erotic without explicit recourse to sexuality and/or love? In other words, can we define it as its own entity while not completely negating previous conceptualizations?

Here is what I propose:

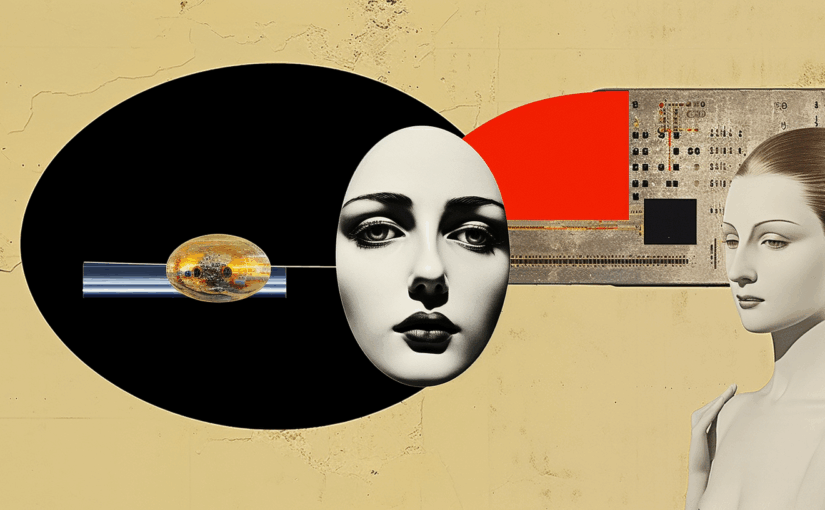

The erotic is a primordial mode of embodied becoming: a generative tension in which desire, form, and meaning arise together through relation. It is dynamic attunement to the interplay (or interbeingness) of unity and difference, where the self moves toward coherence by entering into participatory relation with what is not. The erotic is marked by an insistence toward wholeness; that is, a transcendence not of the body, but of alienation within the self. It is a liminal field of symbolic and affective potentiality where perception and form, self and world, beauty and truth fold into one another without collapse (i.e. Deleuze, Merleau-Ponty, and others). It takes form only through relation, attention, or symbolic resonance. What emerges, whether longing, tension, intimacy, grace, or something else entirely, is not the essence of erōs, but its momentary expression. The erotic manifests through the sustained holding of tension; not to resolve it, but to let it resonate—symbolically, sensuously, deliciously—until meaning begins to take form. In this sense, the erotic animates Being and drives the symbolic intuition of its continual arrival. Importantly, and especially in the context of psychedelic experiences, the erotic does not depend on the persistence of a bounded self, but it does require the persistence of form, relation, and becoming. It is most fully realized when the self dissolves into the very field of becoming it once observed.

Or, more simply, the erotic is primordial desire held open until it becomes form.

This working definition goes a long way toward encapsulating my thoughts about the erotic; which is to say that it’s not necessarily a category of experience, emotion, or behavior, but as a fundamental ontological and aesthetic force that is both grounded and expansive. It’s not perfect, but it’s a start.

Here, “generative tension” becomes the medium through which erotic meaning arises. In a certain sense, we are addicted to tension, but what matters, ultimately, is not the tension itself, but whether the form can hold it. Tension only becomes erotic when it is symbolically or aesthetically contained, even if just barely. This is why sexual tension is not about climax, but about the delay and restraint: the sublime moment just before a kiss. In its degraded forms, tension results in drama, conflict, and chaos; it has no symbolic outlet. In its more refined forms, tension manifests as art, music, love, transcendence; it is tension sublimated into form.

This definition also attempts to invite a certain philosophical flexibility in which difference-as-dynamic (“interplay”) and difference-as-constitutive (“interbeingness”) are both possible, and itself is an acknowledgement of the (erotic?) tension between epistemology and ontology.

If the erotic impulse is ultimately an “insistence toward wholeness”—meaning the self’s continuous questing for the integration or unity of all its disparate parts into a fully realized Being; or we might call it an existential hunger for poiesis—and if the erotic, as I suggest, is “primordial desire held open until it becomes form,” then what of so-called “peak experiences,” especially during psychedelic or mystical states, where the subjective self seems to disappear, where formlessness is form?

Is this a contradiction? I don’t think it is, because the erotic is not located in the ego, but in the structural conditions of relation and form. The erotic, as a field of potentiality, becomes most fully realized (for lack of a better word at the moment) in the absence of egoic tension.

But the lack of egoic tension, as I see it, does not mean lack of all tension. In peak experiences, psychological tension recedes and allows structural tension to be (more) fully expressed. Even in the absence of ego, there is still a distinction between sensation and symbol, form and flux, presence and, we might say, presence-of-presence. Consider this painting by Rothko:

Currently housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Ostensibly, there’s no “subject,” yet the field holds tension between color, edge, and light, to name a few. The subject is the collective interplay and interbeingness of the composition. Likewise, in peak experiences, there is no “I-Self,” but there is still difference without distance, movement without motion, and a symbolic unfolding without self-conscious reflection: pure awareness of the composition, which includes the observer.

(One is also reminded of the Bodhisattva’s observation in the Heart Sutra: “Form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.“)

The intention here is only to offer the briefest of sketches, and it’s entirely possible there are misapprehensions on my part, gaps, or the unintentional convergence of ideas with other thinkers, and I welcome critical—and kind—feedback. For the moment, it suffices to say that that the erotic is both a field and a feeling, a potential and a pattern, a metaphysical “grammar,” and a momentary spark of coherence.